The Ugly Truth: Catching up with Melissa Hedge

When I decided to start painting professionally, I scoured the internet for information on how to get my work out there and grow my business. I found tons of suggestions, but they didn’t explain the process.

Everything said, “Open an Etsy shop,” but didn’t explain how I was supposed to drive traffic to my page. Everything said, “Post on Instagram,” which got me nowhere because it didn’t explain how to utilize hashtags. The advice made it seem like all I had to do was put up a for sale sign and customers would flock to me. Well, that obviously didn’t happen.

There is so more that goes into an art career than your ability to create, so when I was asked to write a guest piece for MilspoFAN, I knew I wanted to give advice on a few topics that no one ever seems to mention, but should.

Thick Skin is Required

Not everyone will like your work, and some may be rather vocal about it. I’ve overheard someone trashing my painting style when they viewed my work in a gallery, I’ve been called a human copy machine, and have even been told that I should just bury one of my paintings. I used to be overly sensitive to criticism until I realized people will voice their opinions on everything, even things they know nothing about. All it took was a little social media experiment.

“Past In the Present II” Oil on Canvas

I showed a group of artists and a group of hobby fossil hunters a painting I’d been working on to get feedback from both groups. I chose to show them my fossilized shark tooth painting because paleontology is one of my hobbies, but it’s a niche subject that most people aren’t familiar with. I asked for honest opinions and didn’t explain anything about the painting. The feedback from the fossil hunters was amazing, but the majority of the artists said I needed more practice because the mushrooms I painted looked terrible.

So, don’t let negative opinions bother you. They don’t speak for everyone because if you put your work in front of the right audience, it can be a game changer. That painting was purchased by a fossil hunter a few months later and I’ve sold several prints since then.

Find Your Sounding Board

Critiques are not the same as criticism and will help you more than affirmations. I love my family and their unconditional support, but I know they won’t pick apart my work the way I need them to. Getting only positive feedback can set you up for failure because you won’t improve and it may give you an inflated sense of skill and expertise. This could lead to some pretty hard reality checks if you ever decide to do competitions or exhibitions. You don’t want that. That’s why a sounding board is so important.

This is a person or group that you trust AND who knows your work and who you are as an artist. You need advice from someone who understands what you are trying to achieve. Otherwise, their well-intentioned advice will ultimately veer you off course. Your sounding board is there to help toss around business and creative ideas, but they are also there to give you honest critiques. Occasionally, you are going to have a really bad idea or will paint something that you’ve convinced yourself is good (when it is, in fact, terrible). Your sounding board will be honest with you and give you constructive criticism in a way that will encourage you, not crush you.

Example: My sounding board said my pug painting lacked my usual quality and looked like ET wrapped in a blanket. He wasn’t wrong and I laughed at the accuracy of his description, but if that response came from anyone else, it probably would have hurt my feelings. I trust that his intent is to help me improve so I went back and fixed the painting. I still see ET in that piece and now that I’ve mentioned it, you probably will too!

Your Love/Hate Relationship with Social Media

I wish I had advice on this, but I still struggle with managing my social media accounts. Sometimes your page visibility is great and your followers are engaging with you and other times it feels like you are just shouting into a void because your page’s reach randomly tanked. The inconsistency makes advertising and sharing upcoming events difficult and makes me want to pull my hair out.

My reaction to Facebook’s algorithm during the 2022 holiday season

Understand that the advice you find on the internet is likely no longer relevant or valuable. If the magic formula was really out there, none of us would struggle reaching our target audiences. The algorithms are constantly changing so by the time people figure out enough of it to give advice, it’s already old news.

That said, there are some things you can do. Posting in groups related to your subject matter can be useful, but make sure you watermark your photos to protect your work. Fossil hunters make up a large chunk of my customer base because they saw my fossil artwork. Posting there to garner sales was not my original intent (I was just proud of my painting), but that was the result.

When you post on your page or in a group, remember that you are trying to sell something so the picture needs to be visually appealing. If you have a cluttered background or the photo is blurry, it doesn’t come off as professional and most will scroll on by. There is a nuisance to advertising so taking a marketing class would be very beneficial in this area.

A note about art groups: They are similar to parenting groups. New artists far outnumber the amount of experienced artists on those pages and the newer artists usually offer the most advice. This tends create a blind leading the blind situation and spreads all kinds of misinformation. Be aware of that when asking for advice in those groups. The people who are responding to you may be offering advice without having the knowledge to back it up. I advise against asking questions regarding copyright laws, taxes, ways to approach galleries, and where to get art prints made (topics I’d love to discuss another time). Those are questions that are better suited for artists you meet within an art organization rather than social media groups (more on that below).

Juried Exhibitions

If you plan to apply to art calls, fellowships and/or grants, then there are some things you need to do first. You need to write a biography, an artist statement, and a CV (I’ll explain these later).

My painting (center right) was included on the advertisement for SMAA’s juried exhibition last year.

You need to know how to ship artwork properly. I was so excited when I was accepted into my first national juried exhibition, but then I panicked. I didn’t know how to ship my painting. I ended up driving from Mississippi to North Carolina to hand deliver it because that wasn’t the time to figure it out. I admitted this to the gallery director who actually walked me to their storage room to show me how other artists packaged their work, so I’d know what to do next time. I opted for a sturdy box and lots of bubble wrap because it’s all reusable. I create a pouch out of the bubble wrap, slide the painting in, and tape it shut so that even if the box gets wet, the painting will be safe.

Side note: I don’t apply to shows that require me to ship my work in late November-December anymore. I had two paintings lost in the mail for about a month and it finally arrived at the gallery almost two weeks late. Thankfully, the gallery was understanding and held them over for the next show, but the risk of shipping delays is too high for me to do that again.

You need to set guidelines for how you select exhibition opportunities. Most exhibitions have application fees and it’s common for the host gallery or art organization to take a sales commission, sometimes as high as 50%. If the potential earnings do not justify the cost of the show, I won’t apply. For me, the fees, shipping, and the commission must be under 40% of the sales price. (But FYI, all those costs are tax deductible).

Once you’ve settled all of that, you can start looking. Make sure you read the prospectus carefully and more than once. It explains what will be expected of you and occasionally you may see a requirement that is a deal breaker. I read one and it felt like a perfect fit until I saw that they were going to charge a $30 unboxing fee for those that shipped their work which was off-putting, so I moved on. If it doesn’t feel right, don’t apply.

Many exhibitions have a theme so it’s important to identify it and only submit pieces that relate to that theme. If you don’t, it won’t matter how amazing your painting is; Your painting will be rejected.

Figure out what areas in the US will be most receptive to your artwork. Galleries want to make sales so they will choose what they believe will sell in their area. As military spouses, you move all around the country and the type of art that sells differs by region. My artwork is predominantly still life and ocean life so when my husband got orders to El Paso, I knew that trying to sell paintings of lionfish and sea turtles in an area that is known for cultural and desert-themed art wasn’t going to work. My art is better suited for coastal regions, so I focus on opportunities in those areas regardless of my current location.

Make sure you submit quality photos! I cannot emphasize this enough. Sending a dimly lit photo or one that shows any part of a background will automatically be rejected. This isn’t social media where you use props and filters to make the photo look more appealing. You need to submit a clear photo of your painting that is cropped to the edge, not including the frame, so only your painting is visible.

Research the jurors if they are listed. What you learn about a juror can give you a better idea of the type of artwork they may select. Admittedly, this part is a little bit of a guessing game, but we all have a preference and sometimes theirs is visible. I look at their body of work and/or in the galleries they represent to get an idea of what they prioritize whether it’s color, style, or a specific theme. If my work wouldn’t fit well in their gallery, I would likely pass on that art call.

The Three Key Documents

If your path involves gallery or exhibition work, you need to write a biography, an artist statement and a CV.

Your biography is who you are (obviously) which you can either write in first person or third person, but it’s up to you on which. If you use third person when everyone else used first person, you will sound pretentious, but if you use first person when everyone else uses third person, you’ll sound like a newb.

This can be tricky because there is no right or wrong, so your best bet is to look at past exhibitions held at that particular venue and read the artist biographies. If the gallery doesn’t have a website, just use your best judgment.

Your artist statement is what and why you create and relates to your body of work as a whole. This is written in first person. Be authentic and brief. This is your chance to explain the reasons behind your work that you want the viewer to know. You will end up with several versions of these two documents since the maximum length varies by application.

Your CV is basically the summary of your life’s work. It is similar to a resume and includes your relevant work history and secondary education, exhibition and commission history, gallery affiliations, awards, memberships, and bibliography. The difference between a CV and a resume is that a CV is all about the facts and you shouldn’t pad it with personal qualities and statements or abbreviate it.

Starting with a thin CV can feel defeating for newer artists, but everyone starts somewhere. I didn’t even bother writing one for a long time because it would have just been my name on an otherwise blank page but I focused on building my CV from the very beginning since it’s often needed for grants and fellowship applications. It took about three years before I felt comfortable enough to apply for my first grant (my CV was just over two pages long), but that work paid off because my application was accepted.

It can be a headache to write and rewrite these documents, but they are essential for certain career paths so make sure you keep track of every festival where you’ve sold your art and every workshop you attend because you may need to write a CV at some point.

Art/Artist Organization Memberships

I started painting right before Covid shut everything down, so I had no idea how to break into the art world. I couldn’t talk with any local artists since we were all in isolation, so I decided to join a few art associations and organizations. I chose one local, two national, and one international to get an idea of how they worked and the benefits of each one.

Through the local organization, I was able to learn, network, and integrate myself into the Mississippi art community. Being a member gave me opportunities to show my work in local galleries, meet other artists, and pick their brains which in turn, made me a better artist. The internet is a great tool, but speaking one on one with someone with a wealth of knowledge and years of experience is irreplaceable. I was also found by a gallery through that affiliation and the owners have been two of my biggest supporters and advocates.

I knew it would be difficult to network through national and international organizations, but they offered exhibition opportunities on a larger scale. I focused on organizations that aligned with my style of painting and who actively advertised their members and upcoming shows. Since I am a realist artist, I narrowed my selection to groups that focused on representational art. Through my memberships and participating in the exhibitions, I’ve been contacted about other art opportunities, had my work advertised internationally, and sold one of my paintings to a private collector.

Unless you have multiple collectors vying for your original paintings, you’ll need to consider generating income from other sources. You can do things like teach workshops, take on commissions, or expand your business to include different products. There are many professional artist organizations that can give you the opportunity to offer workshops to other members and to be a nexus for clients to find and contact you with commission inquiries. You just have to figure out which ones are right for you.

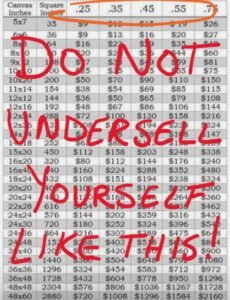

Pricing

This is a big hang-up for most people. There are a lot of factors to consider so you must do your research. Do not use Facebook as a pricing research tool. I guarantee someone will suggest pricing per square inch and post a pricing sheet that starts at $0.25/sq.in. (Which won’t even cover the cost of your materials) and someone else will post some variation of the advice, “time + materials” with no other explanation. Both methods have notable flaws. Pricing based on size alone doesn’t factor in the subject matter. A painting of a single rose should not be the same price as a family portrait just because they are the same size. Pricing based solely on time and materials does a disservice to faster painters and pads the price of the piece for slower painters. You also aren’t accounting for overhead like the cost of your website, advertising, durable equipment, etc. so if you go this route, you need to consider those extra expenses in your pricing.

Some of my paintbrushes cost more than those paintings

Also, neither pricing structure accounts for what is reasonable for your location. If you want to sell locally, you need to look at similar artwork and see where the threshold is for your locale so you don’t price yourself out of that market. You have more flexibility if you sell online, but there are additional costs associated with that like shipping, packing materials, and advertising that need to be factored in.

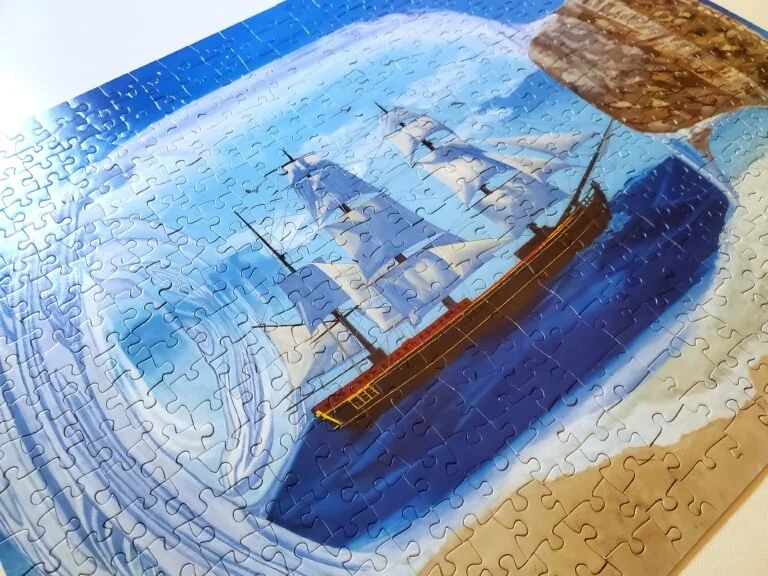

I use a base price by canvas size, then add an additional cost based on the amount of detail. All but one painting was sold to out-of-state buyers so I don’t factor in my location when pricing original paintings, but I do when pricing my puzzles and ornaments since many are sold locally. Keep prices consistent across all platforms so you are not competing against yourself. If you are selling through galleries or on consignment, it may be tempting to raise the price to cover the sales commission, but that may violate your contract and it’s just frowned upon. The commission is the cost of doing business. Someone else is working to sell your painting and that is their compensation. If your painting doesn’t sell, they don’t make anything. That’s the trade-off.

Your skill and experience matter, but there is no standard for how it influences pricing since we all progress at different speeds. What matters is that you are able to defend the prices you set based on your skill and/or experience and that you are comfortable with your prices. And remember, unskilled labor is paid minimum wage, but this is a skilled trade. Compensate yourself accordingly.

Above All Else, This is a Business

The reality is that good artists are a dime a dozen and talent has very little impact on your ability to succeed. What will set you apart is your ability to navigate the business side of your career. You need to create a business plan so you have something to work towards and measurable goals. When I started, my business plan was “paint things, sell things.” That was not a successful business plan. I started to flounder a few months in because I didn’t know what I was working towards so I finally sat down and created a basic business plan.

You need to figure out your goal, how you plan to reach that goal, and what you will need to execute that plan. It’s okay to make changes if you want to take your career in a different direction or if your approach isn’t working. Stay flexible.

I started out intending to only sell original artwork, but since I spent so much time on each painting and my price point was high, it limited my potential customers. I realized that wasn’t going to work. I needed to offer more options at lower price points to widen my customer base.

First, I tried a print-on-demand service. I liked that I could sell different products and that I didn’t have to worry about filling orders myself, but I had very little control over the price and quality of those products. The quality would reflect badly on my business, not the on-demand company so after a few months, I closed that online shop, created my own website, and started working with a brick-and-mortar print shop. They photograph my paintings and print my limited edition prints on both paper and canvas.

Later on, I expanded into puzzles and handmade ornaments. I researched puzzle manufacturing companies for weeks, then ordered samples from each company to feel the quality of the pieces and make sure the images were crisp and vibrant. I chose the company that had the best balance of quality and affordability. Product testing is crucial and believe me, I test everything, even the bags I use to ship my puzzles. I packaged a puzzle and literally threw it around the room for 5 minutes along with some Amazon boxes to simulate the USPS shipping process, just to make sure they would protect the puzzles. I am not advising you go this route since it does require maintaining inventory, but no matter what or how you choose to sell your items, you need to be able to stand behind your work and the products you offer so customers keep coming back.

So remember, being an artist is 20 percent art and 80 percent business. If you do not put serious effort into the business side, then your career will transition back to being a hobby. This is a tough career path, but you were brave enough to go for it anyway. So create a plan, find your support system, utilize your memberships, and pursue your dream!