An Interview with Abby Murray

Tell us a little about yourself, your journey as a military spouse, and where you are today. (Include things like where you have lived, who is in your family, where you grew up, how long you and your spouse have been “in”, or how you met your spouse)

My five sisters and I were raised by a single mother in rural Washington, where I dreamed of going to college to study writing. I met my husband there, but when we met, we had no intention of marrying each other. I was an anti-war protestor and he was in ROTC, preparing to deploy to Iraq; we started arguing in 2001 and are still at it. Except we’ve been married now for almost 21 years. Perhaps we got married to guarantee we could keep the discussion going.

Obviously, my interest in pacifism predates my marriage. It may be part of what drew me to him, but we are both our own selves, with our own histories. He is in the military. I am not. The military, like the civilian world, is made up of people with their own stories, weaknesses and strengths, fears and loves. I have always been passionate about defusing war by understanding the people involved, which means I naturally gravitate toward service members rather than avoid or ignore them.

My mother was a military kid and grew up in Turkey, Chicago, and the American south, but I was not raised in a military family. My mother birthed three kids and adopted three, raising us on her own. My childhood experiences were heavily influenced by her backbreaking work to provide for us. From a young age, I was aware of systems and institutions built keep her from the freedom she deserved. I don’t think my mother intentionally raised me to be interested in revolution, but on reflection, it seems inevitable that it would’ve happened that way. I have been watching resistance play out all around me for my entire life.

How did you become a writer?

When you have five sisters who are all talented (and gorgeous to boot), you learn to find the niche where you can explore unaccompanied and freely, at your own pace. I loved dance, but so did one of my sisters. I loved baseball, but so did one of my sisters. I was trained as a violinist but so was one of my sisters.

No one in my family seemed interested in poetry, which gave me the space to find it. Once I felt how powerful and playful it was, not to mention portable and affordable (it requires virtually no instrument, fees, playing field or equipment), I was hooked, so that freedom to explore independently was crucial. Poetry is subversive and funny and mysterious and brave and scary and weird and authentic and perfect for a broke-ass kid from rural America. I love it. I’m not so insistent anymore on it being “mine” but I think that’s what allowed me to find it at first.

Tell us about how you became the editor of Collateral, a literary journal publishing work concerned with the impact of violent conflict beyond the combat zone. How has the project evolved and where do you see it going?

I launched Collateral when I moved from New York to Washington state in 2015. As a pacifist, writer, and military spouse, I spent a lot of time reading literature grown in the human history of war, but so much of what was published was told by [white, cis-gendered, heterosexual] men. Moreover, the narratives usually focused narrowly on combat experiences, leaving the rest of war’s impact unexplored. I realized: not only were these men often pigeonholed into writing “what sells” (we all know war stories, especially those made into movies, are wildly more popular than actually caring for veterans and civilians changed by those battles) but whole populations and perspectives were being erased. What about the immigrant story? The spouse? The child of a veteran? The civilian who didn’t vote for violence, the nurse, the best friend, the survivor? Where was the reintegration story, the reflective criticism, the awkward realization that beauty finds its way even through terror? These were stories I knew existed but I had more trouble finding them. I wanted to make a place for these voices to nest and thrive.

I started the whole process in partnership with some colleagues and a few students at University of Washington who felt similarly. In 2018, Collateral became independent so it could go wherever I went.

How has your role as a military spouse impacted your work as a writer- creatively, logistically, or otherwise?

What an interesting question! I am now puzzling over what my “role” as a military spouse is. Is it the unspoken, unofficial script that’s defined for me? (I am expected by many to be feminine, nurturing at all times, constantly available, able to adapt immediately to enormous change without complaint, aware and appreciative of both archaic and contemporary protocols & traditions, and possessive of a resiliency that borders on pathological, etc.)

Or is it who I am, which is all I can be? I am nonbinary, compassionate but sometimes unsweetened, overbooked, irreverent, funny, inconvenient, and I swear too much. I am fat and beautiful and queer and difficult and loyal and kind.

I love my husband; I have always wanted him to do well, to be happy, to live as his full self. He feels the same for me. But my places of work do not make even a fraction of the assumptions his workplace does of me. Can you imagine one of my colleagues at the university expecting his husband to call mine and welcome him to the academic department that doesn’t employ him? What on earth would they talk about? Can you imagine me expecting my husband to make cookies for my students? Or travel to conferences where he can be told how to appreciate my work more fully, how to dress, how to host parties, how to speak to his “senior” academic spouses, how to shake hands? That would be absurd. (I’d watch it.)

My time is in constant demand as a parent, editor, instructor, pet owner, repair person, friend, activist, spouse, and writer. Military spouse “roles”, just like any other kind of social pressure or expectation, will take as much time and care as you are willing to leave unguarded. I have to have boundaries, which doesn’t often sit well with military spouse communities. I spend my time cultivating relationships with people who genuinely care what happens to me, and see me as more than my performative functions. This community includes a healthy mix of military spouses and civilians without direct connections to the military.

How do you meet other artists or plug into the local arts scene when you PCS?

Living off post helps. I talk and listen to my neighbors. I crack jokes and bitch openly about what I think ought to be bitched about. I talk and listen to people while I’m waiting in line or checking books out of the library or petting a dog or taking my kid to school or going to a protest or attending a reading. I read local authors. My kid meets people her age, too, and I end up meeting those people’s parents, who introduce me to their own communities.

I ask questions. I get okay with people thinking I sound stupid. I talk and listen to doctors and cashiers and parents and politicians and community leaders and nurses and plumbers and electricians. I look for flyers at bookstores or through my employer or at the Y or at my kid’s school. I teach and listen to my students. I remember I am still part of the last place I lived too, so I always have friends to reach out to, even when the new place feels cold. I tell people I love them. I send letters. I connect the friends I have to each other. I remember that sometimes I have to do uncomfortable things to make the world a more comfortable place.

What’s next for you?

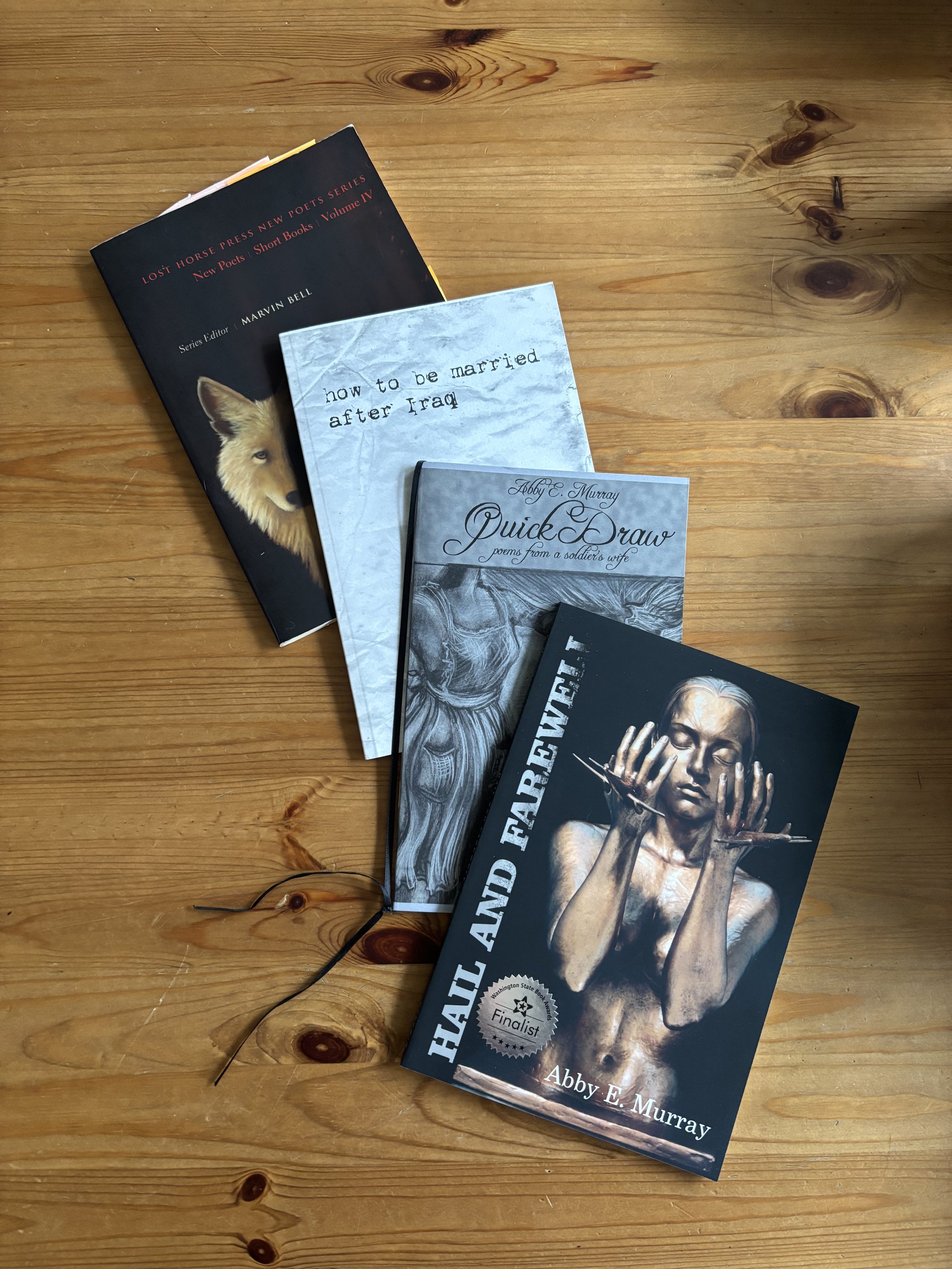

My second book of poems, Recovery Commands, won the Richard-Gabriel Rummonds Poetry Prize and is coming out this fall from Ex Ophidia Press. And this fall will mark the start of Collateral’s tenth year of publishing—tenth! That’s bananas. I get to teach, virtually and in person, for all kinds of organizations, from medical schools to poetry organizations. I have an events page and list of recent publications on my website where people can find out more, register for workshops, or read what I’m sharing.

What is the most practical piece of advice that you would give to other artists?

Be protective of your creativity. Marvin Bell, one of my mentors, gave me this cautionary advice when I was in my 20s. There are so many institutions set up to sap us of our creative energy, playfulness, willingness to share and be changed by what we experience. Protect your creativity from professional ambitions, hungry CVs, the need for acknowledgement or reward, greed, and endless busywork. Write because even when it hurts, it still feels so damn good.

Find Abby online at: